Their dream

Dallas and John wanted to open a museum to showcase the arts and crafts of early Europeans in America. John also wanted to show a British audience that there was more to America than stereotypical depictions commonly shown in Western films popular in the 1950s and 60s.

Cotton Gin, c.1960. We have some beautiful folk art paintings by self-taught artist Clementine Hunter who was born and lived in rural Louisiana. She began painting in later life and produced over 4,000 paintings. 'Cotton Gin' is probably the earliest of her paintings in our collection. (© Cane River Art Corporation)

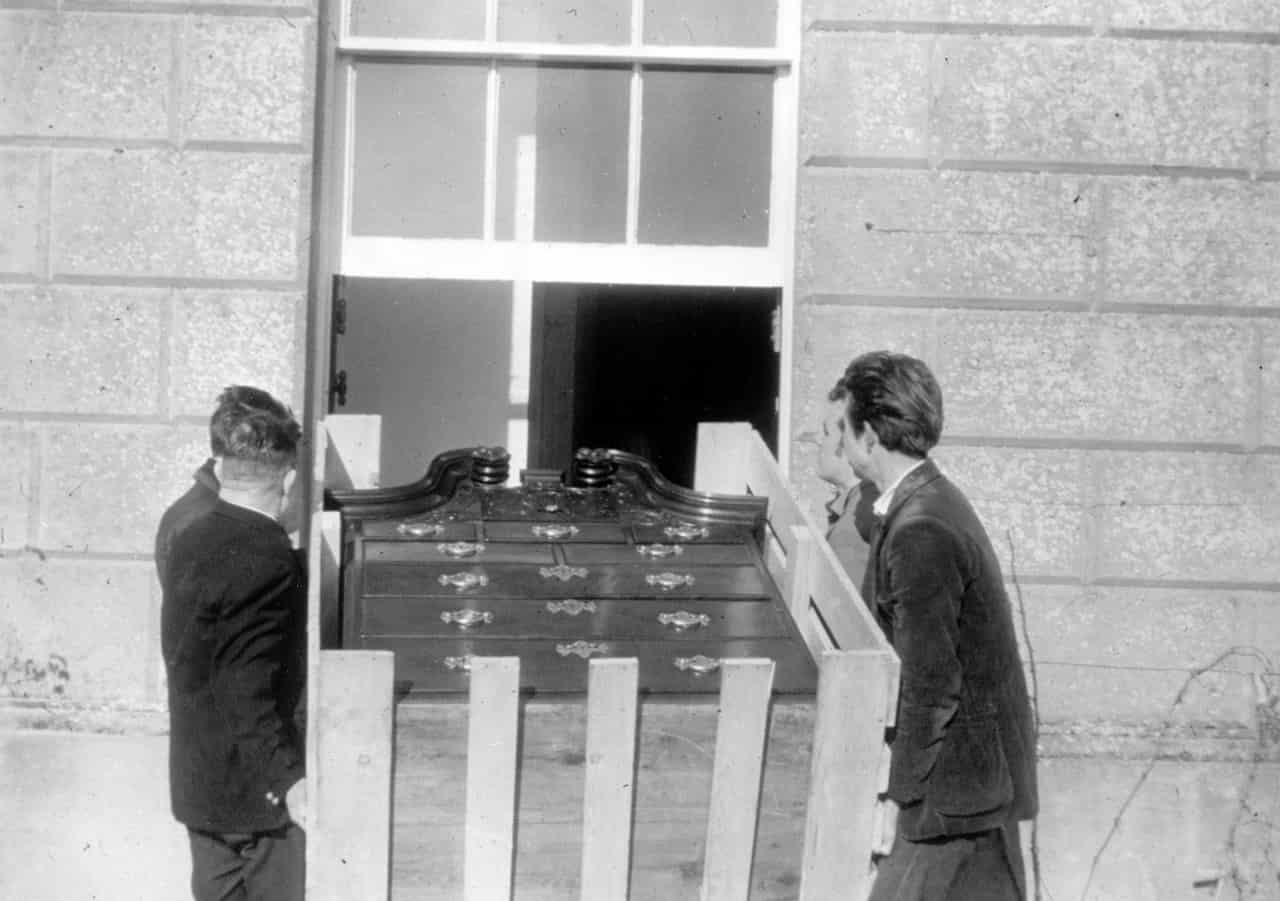

John owned a business supplying antiques to American dealers through a New York show room. He worked closely with London’s finest furniture restorer, Nick Bell-Knight. Together with Dallas they had the perfect mix of ingredients to create a museum in Britain – a passion for history and engaging others with the past, contacts with the best antique dealers, restoration skills, and money. They had the plan and the people to make it happen and now they needed a home for their project.

The Museum – finding the perfect place

The Collection – treasure hunting!

The Opening – inspiring others

The Museum opened on 1 July 1961 and the public took to it from the start. It was well timed, with car ownership increasing through the 1960s, visiting country houses was becoming a major leisure activity.

Find out more

- American Museum & Gardens website

- American Museum & Gardens on social media: @americanmuseumandgardens