Finding a place to belong

When I was eighteen, I left rural Suffolk to move to the city, because that is what gay people in the countryside do, or so I assumed. The city was where I saw all the gay bars and communities. It was where what little of gay history I knew about seemed to happen. I knew more about the history of Soho than I did about any queerness in Suffolk, and while I felt that part of me was rooted in my rural upbringing, it did not feel like a space to which I could truly belong. The idea that the countryside is not a place for queer people seems to persist, partly because we see such a vibrant culture in major metropolitan areas, but also because the history of the countryside has largely been projected through a heterosexual lens.

In helping to promote more visibility of queer people in the countryside, I have begun work on a project called Queer Rural Connections with Dr Kira Allmann. This will bring together interviews with LGBTQIA+ people living and working in the countryside and tell their stories in a live show and film.

Digging into the past

For me, the historical aspect of the project is vital, because it allows us to question our assumptions that rural space is not as welcoming to queer people. But revealing queer history is easier said than done. There are anachronisms and potential ethical issues in trying to place an identity on someone retrospectively who would probably not have used the same terms and language we now use. Nevertheless, that does not mean we should avoid digging into the archives and highlighting cases where there is a clear interest for a queer audience. We don’t necessarily have to label something as queer for it to resonate with us. I would also argue that we can be too concerned with terminology when it comes to our heritage. Yes, we have to be considerate to the past, but we must not be too timid in laying claim to our history or we risk failing those of us alive now, who want to see our experiences and parts of ourselves reflected in those that have come before us. That is why we will create a play and film as part of our project: it allows an ongoing conversation between history and the imagination in which we say 'perhaps it was like this'. First, though we have to find the material. One of the problems with many archives is that the cataloguing bias of previous generations has meant that LGBTQIA+ histories may have been disregarded or buried.

Uncovering Queer rural histories

However, as part of my interviews, I have discovered there are a number of fascinating projects under way.

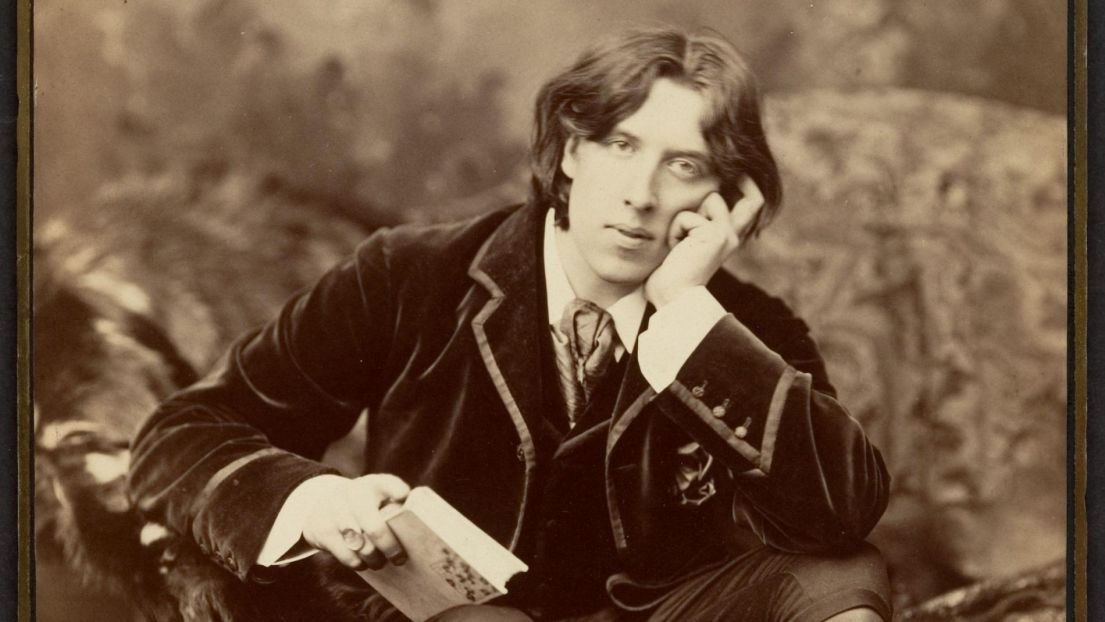

- Volunteers for Pride in Suffolk’s Past, have been uncovering many stories of LGBTQIA+ people making lives for themselves in rural areas. Some of these go back into the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, Nina Layard, from Ipswich, was a pioneering archaeologist and the first woman to enter the Society of Antiquaries, who lived with her partner Mary. Mary and Nina’s diaries are in The Suffolk Archives who set up the project, and will publish a book shortly on their discoveries. Mandy Rawlins, the Community and Learning Officer, explained that the archive had not been representing the queer community, and therefore have been collecting contemporary stories of Suffolk’s LGBTQ+ Community, documenting people’s experiences through a period of monumental societal change towards sexuality and gender identity.

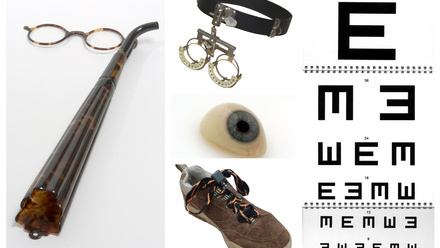

- Broken Futures is run by Reading-based LGBTQ support service, SupportU, with the Museum of English Rural Life. It records the lives of men who were prosecuted under pre-1967 legislation. Many of these stories are by their nature upsetting because of the persecution of the time.

What next?

In watching It’s A Sin recently, it is undeniable that much of LGBTQIA+ history is traumatic, but hence the need for more positive stories, such as that of Nina Layard’s. This is one of the key things I am keeping in mind as we make our show — there are many examples of queer people who have (and are) successfully making a life for themselves in rural areas.

Find out more

- Follow all the project news on Twitter

- Queer Rural Connections project page

- People's current experiences and the decline of queer spaces - Read more of the stories Tim has recorded so far

- Unsung Stories - Discover more about our earlier work on heritage that's been overlooked or pushed to the sidelines

- 'Your Ever Loving G' - Be inspired by Gilbert & Gordon’s love story

- The H Factor - Check out the power of heritage revealed in recent reports

- TrowelBlazers - Further information on the importance of Nina's work in archaeology