Introducing the project

The National Trust is committed to sharing broad, varied and well-researched histories of people. During 2022, we embarked on a collaborative research project, with the University of Leicester’s Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG). This project examined the potential for the National Trust to engage with histories of disability using objects and sites within its collection.

The project asked three key research questions:

- How can we identify histories of disability across National Trust sites and present them in ethically informed ways that enrich everyone’s understanding of both our sites’ histories and their contemporary resonance?

- How can we carry out this work ethically and inclusively, placing expertise derived from lived experience of disability at the heart of the process?

- How can we share disability stories in ways that reflect leading edge accessibility practice?

Working collaboratively

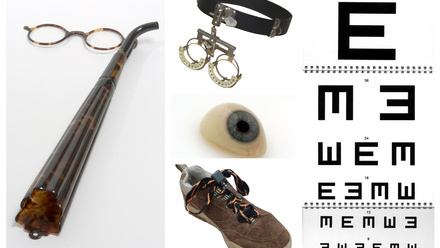

The work was undertaken in collaboration with a group of disability experts who supported two researchers, who were also disabled, to whittle the list of 80 objects and stories submitted by our curatorial teams down to 10 for focused research. The 10 objects and stories covered a range of disabilities and perspectives, including disabled artists, representatives from historic families who lived at some of the National Trust places, and stories of figures who acquired disability later in life. The full list is available on the main project website.

Steering a way forwards

A steering group made up of disabled and non-disabled staff from the National Trust and RCMG guided the project through research and development to decisions on display and the creation of resources to assist with future work. Accessibility was paramount throughout the whole project and the voice of disabled people led this work, literally so in the case of the film which was the main output. The script was written by the steering group and RCMG and voiced by one of the group members. It was also decided to have the British Sign Language (BSL) interpretation included as a main presenter of the film and not purely located in the traditional position of the bottom corner of the film interpreting it all. When there is spoken word from one of the presenters, such interpretation is used but, otherwise, a main presenter is using BSL. This was a progressive change in the role of Deaf people in National Trust interpretation and a significant learning point in the project about equity of experience.

The impact of this project is informing the continual development of our curatorial work at the National Trust.

Find out more

- Everywhere and Nowhere – project website

- Everywhere and Nowhere – University of Leicester introduction

- Disability Histories at National Trust places

- Access for everyone – accessibility at the National Trust

- ‘Any Work’ at the mill (exhibition) – read more about the impact of noise on mill workers in our previous post from the curator of an exhibition at Armley Mills