Textile production was the defining industry of Leeds and the region, and the main driver of the Industrial Revolution. Disabled people have always been part of this industry, working alongside others in the mills and factories. However, their contributions have largely gone unrecognised. Instead, the narrative that disabled people couldn’t work and had to depend on others, whether through charity, the workhouse, or other institutions, took hold around this time. This idea of disabled people as dependent and needy continues to this day. But it’s not the whole story.

'Any work that wanted doing' is an exhibition which brings the voices of disabled people from the past and the present together. Disabled artists have responded to research into the hidden histories of disabled textile mill workers. Their art is on show, until the end of January 2024, amongst the collection of textile machinery at Leeds Industrial Museum at Armley Mills. This is particularly fitting because Armley Mills was once the largest woollen mill in the world.

John’s story – ‘any work’

The title of the exhibition, ‘Any work that wanted doing’, is taken from the testimony of John Dawson of Leeds, who gave evidence to the Factories Inquiry Commission of 1833. This was one of the parliamentary commissions set up to look into working conditions in the mills and factories. They were particularly concerned about young children working long hours in the mills.

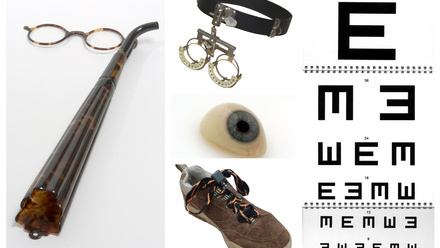

John Dawson was one of a number of disabled workers who described the toll that mill work had taken on their bodies. Long hours, repetitive tasks in awkward positions, and carrying heavy objects led to damage to many workers’ limbs, while the dusty, unventilated premises caused lasting respiratory disease. John had started working in a flax mill at the age of six or seven, about 20 years before the commission met. He worked as a doffer, replacing full bobbins of spun yarn with empty ones on the spindles of spinning frames, and recalled:

My knees were quite bent at that time, as bad as ever they have been: I did not see any doctor about 'em until after we left Clayton's. We staid there between three or four years; until my father died: he was an overlooker there. I was set to spinning and doing jobs; any work that wanted doing.

Sarah’s story – winding to weaving

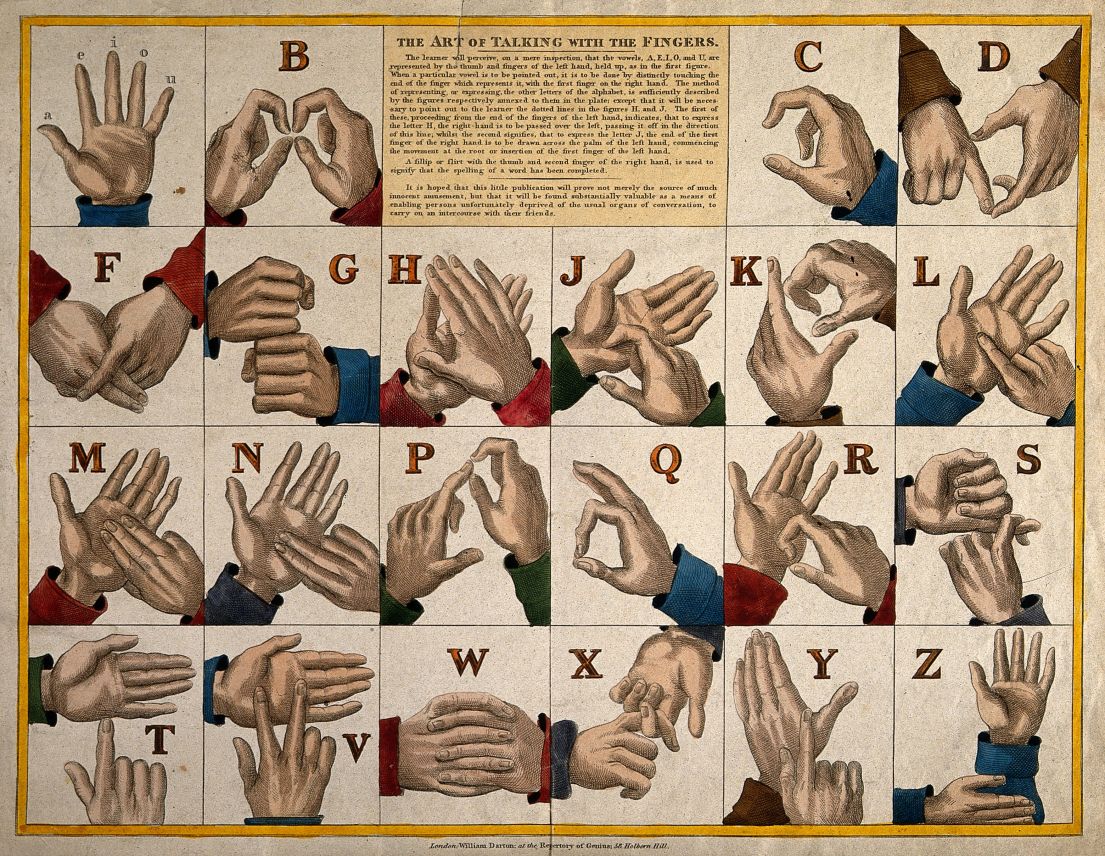

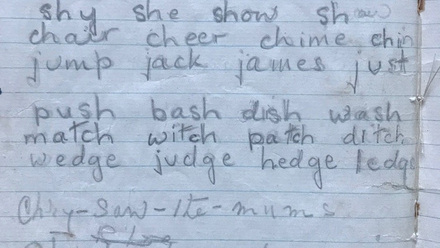

As well as those workers who became disabled through mill work, there were other Deaf and disabled people who took up jobs in the textile factories. Sarah Hartley was one of these. Sarah had previously attended Doncaster’s Yorkshire Institution for the Deaf and Dumb, as it was then called, from 1830-35.

The school carried out a series of surveys in the 1840s and 1850s to find out the occupations of their ex-pupils. The school aimed to show that their educational methods were turning out useful members of society. The ‘Results of an Inquiry Respecting the Former Pupils’ showed that these young Deaf people had entered a wide range of occupations, including jobs in the textile industry. The survey responses provide an insight into Deaf people’s working lives, and to attitudes of the time. Sarah’s manager at Dickinson and Barraclough, a worsted manufacturer in Leeds, described her as being somewhat irritable, although this might have reflected other workers’ impatience and communication barriers.

Sarah later became a stuff (worsted) weaver, a promotion from winding bobbins. She married another former pupil from the school, George Stables. They lived in cramped workers' cottages in the narrow yards of Hunslet, an area full of mills and workshops.

The stories continue

In her artwork, Integrated Society, Ria explores ideas of integration; of disabled and non-disabled people living and working together. Ria lives in a flat in a converted textile mill in Morley, on the outskirts of Leeds. There are other disabled people living there, alongside non-disabled residents. For the exhibition Ria made a long banner, screen printed with photos of the architectural features of Morley’s mills and nearby streets.

Textile mills have always been places of integration, where disabled people worked alongside others. This might not have been taken into account by mill owners of the past, or by the companies who renovated my building, but still integration continues.