Voices from the river

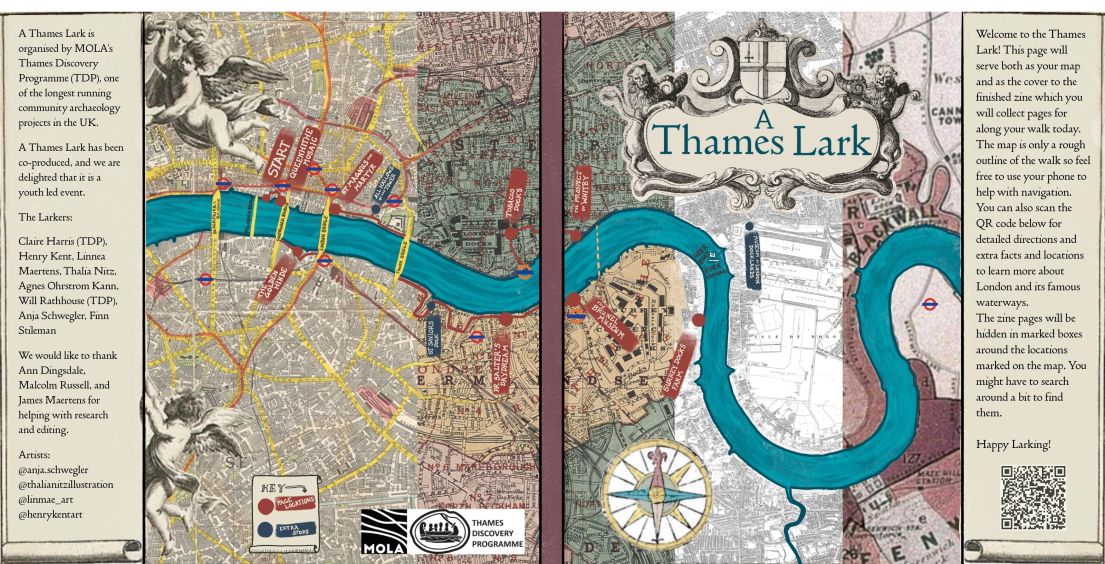

Thames Discovery Programme are passionate about sharing stories from the Thames and we were delighted to be part of New Wave for Heritage Open Days 2022, working directly with 18-25 year olds to produce an exciting Thames-inspired event. ‘A Thames Lark’ aimed to amplify unheard voices from the past, unwrap hidden stories, and allow participants to explore an alternative history of the River Thames. Event participants followed a self-guided trail along the river, collecting pages from a special edition zine that had been designed and created by the group.

Crazy’ labels

One of the stories the group wanted to share was that of Madame Marie Celeste De Casteras. Celeste’s story had been discovered and researched by one of the Thames Discovery Programme’s long-term volunteers, Ann Dingsdale. Ann’s research uncovered a fascinating tale of a passionate and determined woman who refused to be constrained by expectations of her time. Although Celeste was born over two hundred years ago the words used by men in power to describe and denigrate her are familiar today. Celeste was dismissed as “excitable”, “not in her right mind” and told by lawyers that she was mad; her noncompliance portrayed as insanity. The trope of the crazy woman has been used to silence women for generations, but Celeste refused to be conquered!

Celeste’s story

Written by… Ann Dingsdale, Thames Discovery Programme volunteer

Aristocratic beginnings

Madame Marie Celeste De Casteras was born to a French aristocratic family in 1808. In 1841 she came to London and married Luigi Sinibaldi. He taught Italian and Celeste became a milliner. One of her customers was the Duchess of Buccleuch who kindly gave financial help to the young Sinibaldi family when they, like so many, lost their savings in the railway shares stock market scam.

Apprenticeship

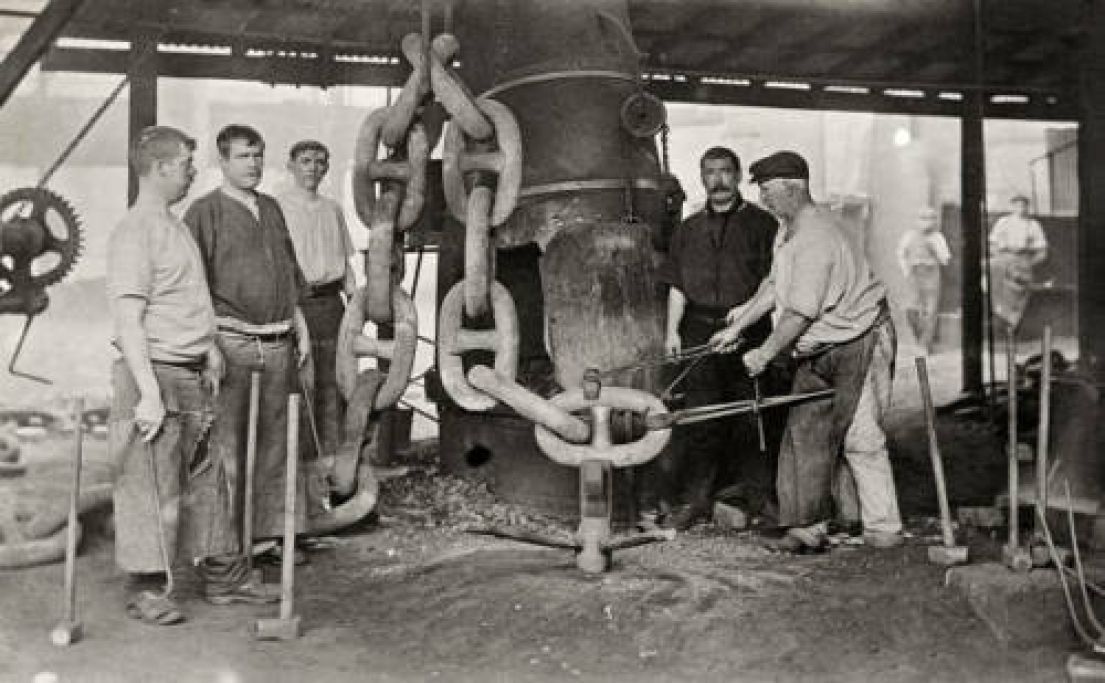

Breaking the chain (of command)

Nevertheless, that same year a chain made with Sisco’s machine was tested by the Admiralty. The chain nearly broke the testing machine. Unfortunately, the “excitable” Celeste rushed to the press with a glowing account. Peeved, the Admiralty refused to publish the report because she had not observed protocol.

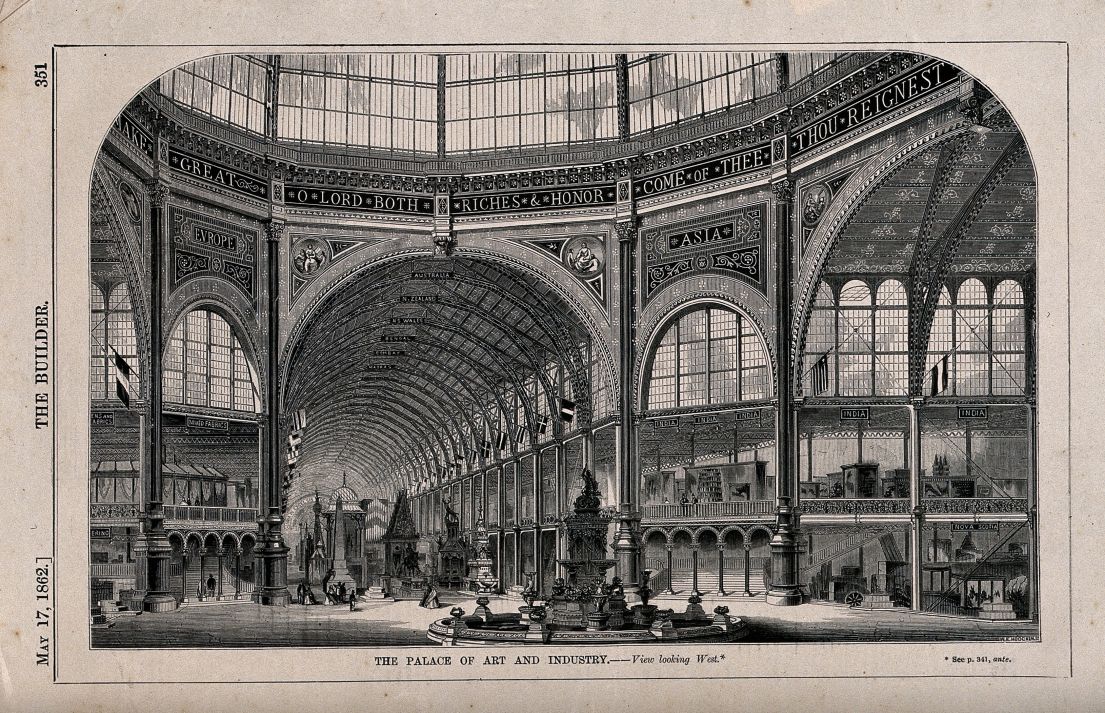

In 1855 Luigi, her husband, disappeared. Undeterred, Celeste moved to London with her three children and continued blacksmithing. Eleven years later, in 1862, Celeste went with Sisco’s invention to the International Exhibition. An article of the time mentioned Mdm. Sinibaldi and the successful chain test, commenting that despite the Admiralty’s rejection,

Unconquered

Find out more

- A Thames Lark - Discover more stories

- Thames Discovery Programme

- Blog - Search for more stories of Extraordinary Women

- New Wave - Learn more about our youth engagement programme

- The Heritage Alliance's Heritage Heroes awards