Our eyesight is one of our most precious senses, the one a majority of adults say they most fear losing. Visual impairment, however, often occurs alongside other disabilities. In their working practice optometrists* may have to cater for various patient needs. Furthermore, as primary care providers on the local high street, they may be strategically well-placed to identify additional health problems at an early stage.

*What’s an optometrist?

There have been spectacle makers in the UK since at least the 15th century and opticians, specialising in the fitting and supply of vision aids, from the early 18h century. Optometrists are medical-related healthcare professionals who are specifically qualified to test sight and examine the eye for disease. They may work in community practices, hospital clinics or visit you in your own home. Originally called ‘ophthalmic opticians’, they were distinguished from the 1850s by their ability to use an ophthalmoscope. Their role has expanded in recent decades, for instance many optometrists are now qualified to prescribe ophthalmic drugs or treat minor eye conditions.

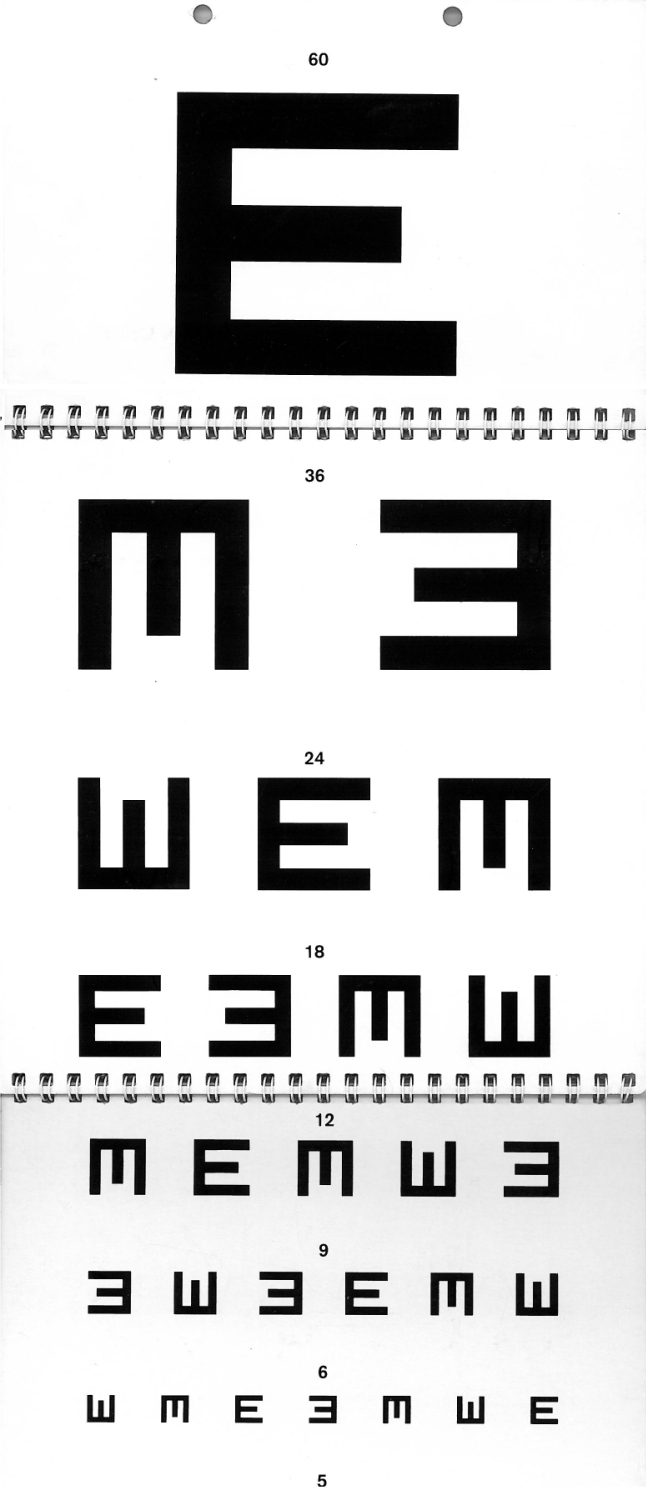

Two fish and a tumbling E

Test letters have been used since first introduced for the Dutch military in 1862, but not all patients can read. They may be too young, they may not speak the required language, they may have been deprived of education in their place of upbringing, or they may have developmental difficulties or learning disability. The E symbol can be used in such circumstances. The patient does not need to know it as a letter E. To them it may simply be three prongs pointing to the left, to the right, upwards or downwards. By handing the patient a template of the same shape the optometrist can ask them (or use indicating gestures) to orientate it in the same direction as the symbol on the test chart. The patient does not even need to speak, just move the template. If that works, they can progress to a smaller letter thereby allowing measurement of the patient’s visual acuity. It is no longer called the ‘Illiterate’ E as that would now be considered insensitive and the term ‘Tumbling E’ is used instead.

Other cultures use easily-recognised everyday things in a similar manner to test vision. For example in Japan a symbol of two swimming fishes features on some test charts. Is the fish swimming to the left, to the right, diving to the ocean bottom or jumping out of the water?

Holding steady

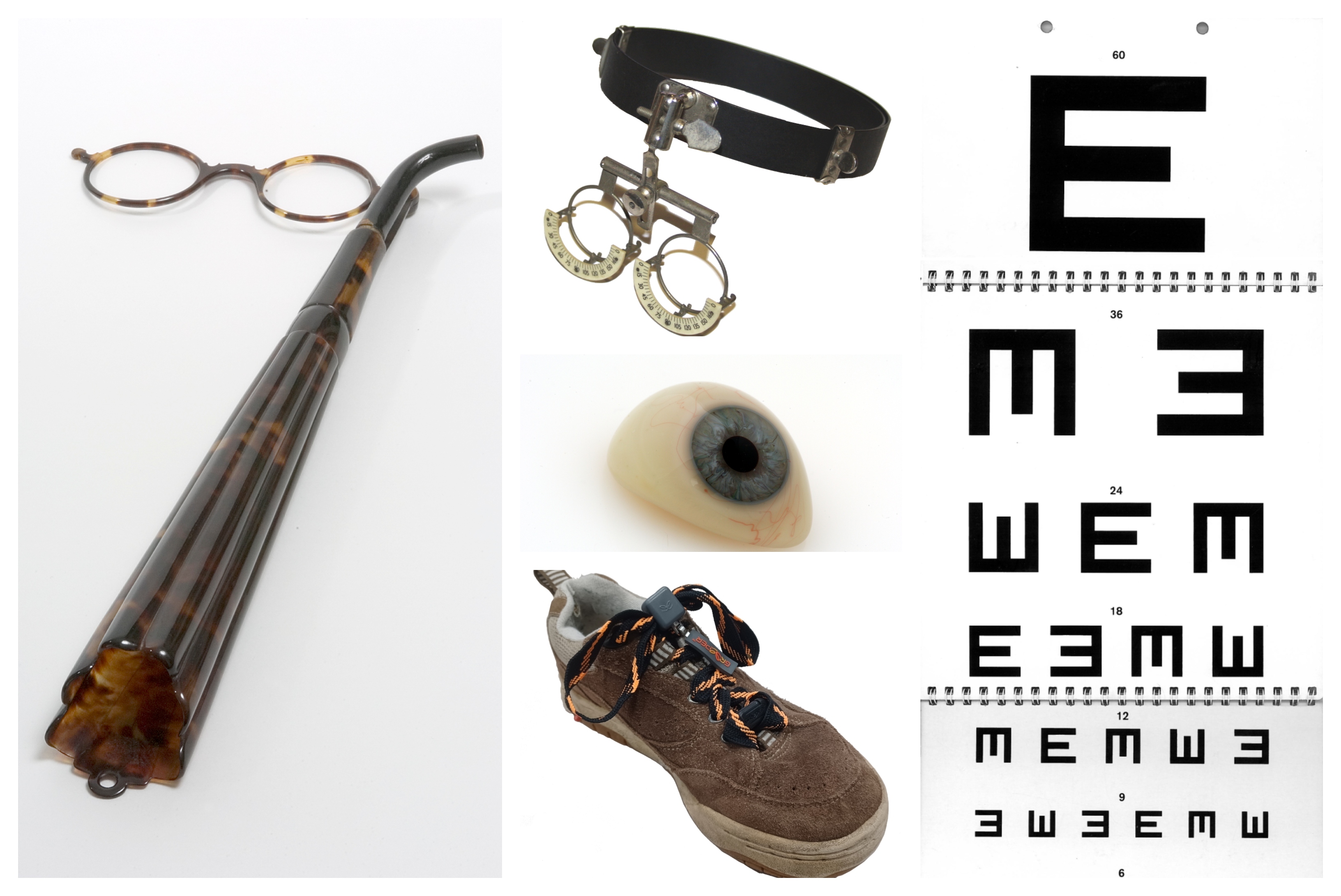

An optometrist drops trial lenses into a trial frame worn by the patient to see what difference it makes. “Is it clearer now?” Some nervous patients may be uncomfortable with this frame gripping their nose, and for some with sunken features, as may happen with patients with Down’s Syndrome, the frame may not balance of its own accord. The solution is to support the frame on a headband as with this example from the 1950s. It will stay in place even for those patients who may make sudden involuntary movements. If the practitioner also wears a headband instrument such as an inspection light, mirror or ophthalmoscope, it adds a sense of equality to the encounter, lessening the potential stress levels. The sight test is usually conducted in a darkened environment, but adaptations may be required if this would be distressing for a patient.

Look and listen

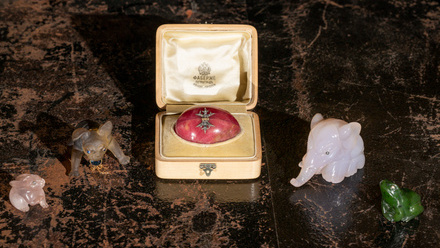

Multi-sensory impairment is very common, particularly in ageing patients. That is why it can make sense for many high street optometrists to work alongside audiologists, offering sight tests and hearing tests on the same premises. Here is a lorgnette from the early 19th century, a form of vision aid on the end of a long handle, so-called from the French verb ‘lorgner’ (to stare at something). This is no ordinary handle, however, for it also incorporates a hearing trumpet. Now Grandma could ask for the little children to be brought to her for inspection, and hear what they had to say to her too. It may have been both exciting and intimidating for those kids.

By the 1950s hearing aids could be incorporated within the sides of a pair of spectacles although it made them bulky. A refined version of the technology is present in augmented reality glasses, which may benefit a disabled or a non-disabled person alike, for instance by allowing them to listen to music on the go.

Self-fastening shoe laces

These look like ordinary shoe laces, tied in a knot, but in fact they fasten more simply by a plastic toggle. It can be important to the self-esteem of a person with manual dexterity problems to be able to fasten their own shoes without it looking like they need special provision. Invented by an optometrist in his garden shed, this version from 2009 also includes a high-visibility stripe, serving both to keep the wearer safe when walking along the roadside or in low lighting conditions and to add a touch of fashion to their appearance, which may help motivate them to use the product.

Shoe laces with an easy to fasten toggle and snazzy design to appeal to all. (© College of Optometrists)

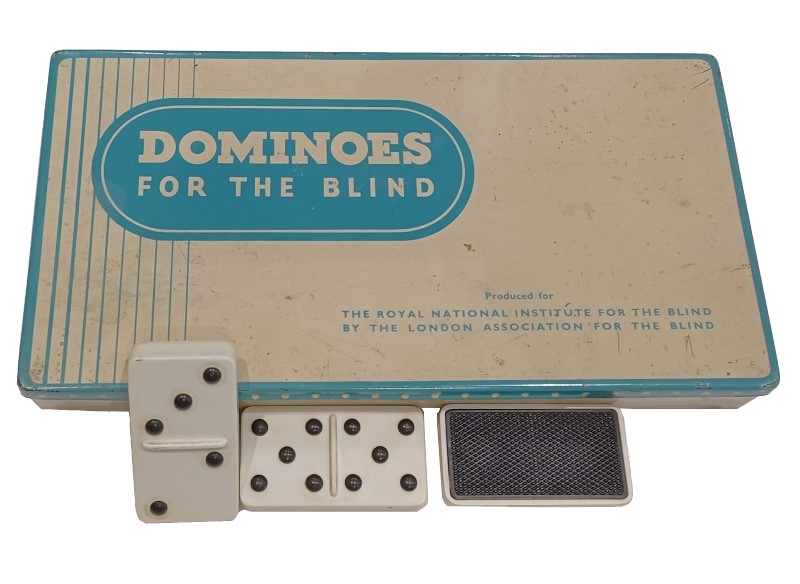

Raised dots and dominoes for all

Only a minority of registered blind people can read Braille, but the principle of raised dots can be used more simply. This set of dominoes from the 1960s is the perfect example because the playing pieces of the game can be used equally by someone with or without visual impairment. The textured reverse would help not only differentiate the playing side from the other side, but also prevent those tiles that were in play on the table from moving whilst being felt. We would no longer refer to these as being ‘for the blind’ as it is now recognised that that sort of language depersonalises someone with differing abilities, so we would now speak of something being designed for ‘blind people’, although some of our counterpart vision charities in the USA have not yet caught up.

Artificial eyes

Making ocular prostheses (artificial eyes) was still a standard part of optometry training up until the 1980s. It is now so specialist that it has become a profession in its own right, that of the ocularist, many of whom have a background as dental technicians. There are so many artificial eyes in our museum that we like to say it is the only museum where the exhibits look at you rather than the other way round.

It used to be a well-worn joke to ask optometry students to perform ophthalmoscopy (examine the interior of the eye) on a patient with an artificial eye and see how long it took before they realised. Many patients, however, have enjoyed being in on this joke. There are many accounts of patients removing their eyes as a party-piece and some make no attempt to disguise the fact that their natural eye is missing, filling the socket with the emblem of their military regiment or favourite football team. In this way difference can be celebrated rather than demand sympathy. To make an artificial eye that can actually see is the next challenge and medical trials involving video implants are already allowing patients to distinguish between light and dark and detect moving shadows.

One of the many artificial eyes looking back at you in this museum. (© College of Optometrists)